This morning, the Georgia Court of Appeals issued a decision in the case of Garcia Trucking v. Jose Sandoval. While there is no new standard announced in this decision, there are some practical lessons to be drawn from it, most especially in light of the changes to the Board Rules regarding filing of the WC-1 and decisions regarding whether to accept or controvert your cases.

First, the decision: Sandoval reported an injury that occurred in October 2014. There is a dispute as to when an injury was reported but the employer knew or had reason to suspect and investigate a possible injury given that Sandoval was at the time missing work. There was dispute as to whether Sandoval had a pre-existing lower back problem and received some degree of medical care for that condition prior to the injury. At trial the ALJ found the claim to be compensable. The claimant was awarded assessed attorney fees against the employer for unreasonable defense of the claim. The First Report of Injury denying the claim was filed more than 21 days from the notice of injury and so penalties were assessed for that failure but attorney fees were not awarded for the late filing of the WC1. On appeal the Appellate Division of the State Board of Worker’s Compensation pointed to the factual disputes and the closely contested issued in its decision to uphold the filing of compensability but to reverse the award of assessed fees. Sandoval appealed to the Superior Court seeking to have the assessed fees reinstated. The Superior Court obliged, citing an error of law in which the State Board’s failure to cite evidence about the late filing of the WC1. The Superior Court reasoned that failing to cite evidence meant that there was no evidence and so the Superior Court was not bound by the “any evidence” standard of review. The Court of Appeals reversed the Superior Court , reinstating the award of the State Board and denying Sandoval’s request for assessed fees. The Court noted that the ALJ assessed fees for unreasonable defense and not for the late filing of the WC1 so when the Appellate Division of the State Board found the defense to have been reasonable, the ALJ’s award, at least as to attorney fees, was reversed. In other words, there WERE facts in evidence upon which the Board based its findings to deny the assessment of fees. The Court made special notice that the assessed fees were NOT based on the late filing of the First Report of Injury.

Second, practice pointers from the decision:

1) Factual determinations are initially made by the ALJ but can be accepted or rejected by the State Board’s Appellate Division. If you don’t get the facts in your favor before you get to the Superior Court you need an error of law to change the decision. As a practical matter, this means that most Superior Court appeals are going to be bound by the any evidence rule.

2) If the Superior Court reverses a decision, chances are that the Court of Appeals will accept the Application for Discretionary review if there is evidence to support the award of the State Board.

3) You and your Counsel must know the difference between a factual issue (disagreeing with HOW the Judges viewed the evidence) and a legal issue (failure to apply the correct standard)

4) Recent changes in the Requirements for filing the WC1 and in the necessity to make a decision on accepting the claim can serve as an independent basis for an assessment of attorney fees and will be used by Counsel for the Injured worker any time that it is applicable.

a. File the WC1 within 21 days of the notice of injury. For Employers this means reporting the injury to your carrier as soon as is possible and working diligently to assist in the investigation

b. If you are uncertain as to whether the claim is or should be compensable, mark the WC1 as medical only, file it within 21 days from notice of the injury and provide authorized care while the investigation is ongoing

c. If you decide later that the claim should not be compensable, file a WC3 to controvert.

Call on us if we can be of assistance.

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

Friday, March 8, 2019

Tuesday, March 5, 2019

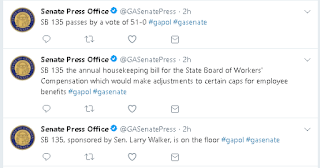

Last week we provided to you a summary of legislation pending before the Georgia General Assembly pertaining to worker’s compensation in Georgia. That legislation is now one step closer to being law as it has passed the Georgia State Senate this afternoon and is now headed to the Georgia House of Representatives for consideration. As mentioned the legislation raises the maximum TTD rate to $675.00 per week, the Max TPD rate to $450.00 per week and the Death Benefit to $270,000.00. The most consequential change, however, is that relating to the 400 week cap on medical benefits. While the 400 week cap still applies, the legislation does carve out an exception for Durable Medical Equipment, joint replacements, etc. The wording of the statute, inserting a new provision specifically covering all injuries on or after July 1, 2013, would mean that the expansion of medical entitlement for these precise categories would operate retroactively. If, therefore, you have cases that would be affected by this legislation, you might wish to conclude them by stipulated settlement now. The average claim, will not, however be affected.

Also of interest is House Bill 474 which would provide limits and administrative requirements on the Rulemaking powers of the SBWC. Currently O.C.G.A. §34-9-60 provides the statutory authority for the State Board of Worker’s Compensation to promulgate rules as to HOW the Board will operate and what is to be done pursuant to the Statutes. That rulemaking authority must be carried out consistent with the Statute or the rule is subject to challenge. In other words, the Statute controls. House Bill 474, similar to an effort passed by the legislature last year but vetoed by then-Governor Deal, would have made the Board subject to the Administrative Procedures Act. This effort would require publication of proposed rule, public comment and then review of the rule by legislative committees BEFORE any such rule could take effect. This is simply new packaging to last year’s rejected solution and is not likely to be passed. Instead, House Bill 474 is being sent to the Advisory Committee for comment. The entire purpose of the Advisory Committee structure is to assure that the Georgia Workers’ Compensation System being run by consultation and consensus. House Bill 474 would seem to be an effort to require advice and comment when such has already been given by the very parties who know what proposed changes would do to the system. We will let you know what becomes of this bill in the future. We do not expect it to be passed this year.

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Thursday, February 28, 2019

2019 Georgia Worker's Compensation Legislation

The package of legislation dealing with changes to Georgia’s Worker’s Compensation system was finally introduced yesterday in the Georgia Senate. The bill is the SBWC sponsored package that came out of the Advisory Committee Process. This bill has, therefore been vetted by representatives of injured workers, employers, insurance companies, Medical personnel and Defense attorneys . As such, this represents as close to a consensus as we can get in contentious times. This bill will need to be passed by the Senate and by the House and then signed by the Governor in order to become law on July 1, 2019. The only forseeable impediment at this point is whether the Legislature has enough time left in the session to get the bill passed by both chambers.

The changes to the Worker’s Compensation Act include:

1) Elimination of Director Emeritus position (a retirement benefit item and so just an “inside baseball” sort of thing)

2) Increasing the TTD maximum to $675.00 from the current $575.00

3) Increasing the TPD maximum to $450.00 from the current $383.00

4) Increasing the Death Benefit to $270,000.00 from the current $230,000.00 where the spouse is the sole surviving dependent; and

5) Amending OCGA §34-9-200 dealing with the 400 week cap on medical treatment for non-catastrophic injuries.

The last item is the most significant change in the legislative package. The 400 week cap was intended to provide predictability for non-catastrophic claims, most especially in regards to settlement and potential MSA issues. The problem was that this limitation was unfair to employees who had injuries that required joint replacements, prosthetics, Spinal Stimulators and even eyeglasses, hearing aids or mattresses that have known and predictable expirations on their usefulness. For example current technology for a knee or hip replacement might be 20 years but for younger person needing such, they could expect to need 1 or two replacements over the course of their lives, long after the 400 week medical cap had expired.

Assuming that the legislation is passed and signed into law, there will need to be an adjustment in expectations and exposures for injuries occurring on or after July 1. 2019. For those injuries which occurred prior to July 1, 2013, the 400 week cap never applied. For those injuries occurring on July 1, 2013 and through June 30, 2019, the 400 week cap applies regardless of the change. Those injury dates will need to qualify for catastrophic status to remove the cap so for that 6 year period, this will be the next area of contention.

Look for more updates as the Legislative Session continues

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

CASELAW UPDATE - Scheduled Rest Break and Reasonable Ingress & Egress

It often seems like the Courts speak through an inexpert interpreter. Part of the problem is that we look for the result of the case and not to how the Court got to that result. The other problem comes from the attempt of the Court to reconcile different lines of authority that have developed over time, especially when that authority involves other principles of law.

This morning, February 26, 2019, the Georgia Court of Appeals issued a decision in Daniel v. Bremen-Bowdon Investment Co.,. This case, and the case upon which it relies may prove to have far-reaching effects on Georgia Worker’s Compensation.

Ms. Daniel was employed as a seamstress and was taking a scheduled lunchbreak. During that break she was permitted to leave the premises and do whatever she pleased with her time. She intended to go home for lunch but on the way to the parking lot, was injured. The problem for her was that to get from her work station to the parking lot, she had to cross a public street and traverse a sidewalk.

In order for an injury to be compensable, it must 1) Occur in the Course of the Employment and 2) Arise out of that employment. For an injury to be IN THE COURSE of the employment, the employee must be WHERE they are supposed to be WHEN they are supposed to be there. So that one looks to the TIME and PLACE that an injury happens. This usually means that an employee injured while going to and from work is not IN THE COURSE of his employment. For an injury to ARISE OUT OF the employment, the Employee must be doing something in furtherance of the employer’s business. This is a causal connection between the employment and the injury. An injured worker must prove both IN THE COURSE OF and ARISING OUT OF in order for her injury to be compensable.

Exceptions/clarifications to these rules have developed over time. This is where the different lines of authority problem comes into play. The Scheduled Rest Break Defense asserted by the Employer to the Compensability of an injury is meant to recognize that the Employer does not have control over the Employee during the scheduled break and so injuries occurring during such a scheduled break are not compensable. However, historically, the employee’s injury might still be compensable if the injury occurred during a “reasonable time for ingress and egress” to the employment premises. That changed in November 2018, when the full court of the Georgia Court of Appeals decided Frett v. State Farm Employee Workers’ Compensation. Ms. Frett was also on a scheduled break but was injured while in an employee break room on the employer’s premises when she was injured. That Court declined to graft onto the “Scheduled Rest Break Exception” the “Ingress and Egress” Doctrine. In other words, while the Scheduled Rest Break would have meant the injury was NOT compensable, the Ingress and Egress Doctrine would have meant that the case WAS compensable. The Frett Court declined to apply the exception to the exception as it felt that they lacked the authority to do so. Ms. Frett’s injury was deemed not to have arisen out of her employment.

“In our view, any decision to apply the ingress and egress rule to the scheduled break exception should be made by our Supreme Court, particularly because the Supreme Court has never expressed its view on the ingress and egress rule generally.”

So, while ruling against Ms. Frett, the Court invited the Supreme Court to take a look.

That brings us back to Daniels v. Bremen-Bowdon. The Daniels court noted the Court’s disapproval of the previous authority in Frett v. State Farm and decided that the Ingress and Egress Rule does not apply to the Scheduled Rest Break scenario. Judge Goss, who joined the Majority opinion in Frett, wrote the opinion in Daniels and was joined by Judge Brown who did not participate in Frett. Given the rules of the Court of Appeals, the Daniels decision is known as “physical precedent” (binding fo r this case) but is not “Binding precedent” (good authority on which future litigants must rely).

All of this is a confusing way of saying that changes may be afoot. First, in both Frett and Daniels the ALJ initially found the claims to be compensable. In both cases, the Appellate Division of the SBWC found the cases to be NOT compensable in both cases on the interplay between the scheduled rest break and the ingress and egress doctrine. The Court of Appeals, accepting the factual determinations made by the SBWC looked to potential legal error in the refusal of the SBWC to apply the Ingress and Egress rule at a time when the Employee was free to do whatever the employee wanted on a scheduled break. The Court of Appeals, generally bound by the “any evidence rule” is accepting the SBWC decisions to the extent that they do not clearly contradict established caselaw. Neither the Georgia Supreme Court nor the Georgia General Assembly have made their views known.

Even Judge Yvette Miller, formerly an ALJ for the SBWC, is asking for the Supreme Court to step in. She wrote, in her dissenting opinion in Frett :

“But I certainly agree with the majority that the conflicts between the two lines of cases cannot continue, particularly because injuries implicating both the scheduled break rule and the ingress/egress rule arise far too often. And as a former director and appellate judge of the Board, I am acutely aware of the need for employers and employees—as well as the Workers' Compensation bar—to have clear direction in the law. “

As this decision shakes out and the full contours of the developing authority become known, we will keep you updated.

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Thursday, October 18, 2018

So...Can We Drug Test or Not?

Post accident drug testing has been a valuable tool in the toolbox for employers wishing to promote a safe work environment. Such testing has also provided a solid defense to otherwise compensable claims if the employer could establish the presence of drugs in bodily fluid samples obtained within a certain period of time after the injury occurs. Some states such as Georgia even provide for premium discounts if the Employer qualifies as a Drug Free Workplace.

So, when The US Department of Labor published a rule entitled “Improve Tracking of Workplace Injuries and Illnesses – Employee's right to report injuries and illnesses free from retaliation” many employers began to question whether an employer could safely continue their Drug Free Workplace Program. or use post-accident Drug Testing. The chilling effect of the proposed rule was real even if the response was an overreaction. Indeed, even under the tighter rule issued in October 2016 before the end of the previous administration, the guidance offered by OSHA provided:

The rule does not prohibit drug testing of employees, including drug testing pursuant to the Department of Transportation rules or any other federal or state law. It only prohibits employers from using drug testing, or the threat of drug testing, to retaliate against an employee for reporting an injury or illness.

Employers may conduct post-incident drug testing pursuant to a state or federal law, including Workers' Compensation Drug Free Workplace policies, because section 1904.35(b)(1)(iv) does not apply to drug testing under state workers' compensation law or other state or federal law. Random drug testing and pre-employment drug testing are also not subject to section 1904.35(b)(1)(iv).

Employers may conduct post-incident drug testing if there is a reasonable possibility that employee drug use could have contributed to the reported injury or illness.

Still many abandoned post accident drug testing completely, lest in practice they venture too close to the line and be accused of retaliation.

Last week, on October 11, 2018, the previous rule was rescinded and a new rule published in its place. That new rule can be found here: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2018-10-11 . This clarification emphatically states: “To the extent any other OSHA interpretive documents could be construed as inconsistent with the interpretive position articulated here, this memorandum supersedes them.”

As if to emphasize the point, the “clarification” reads:

The purpose of this memorandum is to clarify the Department’s position that 29 C.F.R. § 1904.35(b)(1)(iv) does not prohibit workplace safety incentive programs or post-incident drug testing. The Department believes that many employers who implement safety incentive programs and/or conduct post-incident drug testing do so to promote workplace safety and health. In addition, evidence that the employer consistently enforces legitimate work rules (whether or not an injury or illness is reported) would demonstrate that the employer is serious about creating a culture of safety, not just the appearance of reducing rates.

You can see from the language used that while drug testing is explicitly permitted, that employers would still be well advised to use such testing not solely for the purpose of reducing rates but also to promote a safe work environment without dissuading employees from reporting injuries. In this respect, the language of the clarification is quite similar to the language of the rule published at the end of the prior Administration. What is really new in the “clarification” is additional suggestions or guidance which encourages employers to take positive steps to great a workplace culture that emphasizes safety and not just rates. Some options:

• an incentive program that rewards employees for identifying unsafe conditions in the workplace;

• a training program for all employees to reinforce reporting rights and responsibilities and emphasizes the employer’s non-retaliation policy;

• a mechanism for accurately evaluating employees’ willingness to report injuries and illnesses.

One of the more practical suggestions for a permissible drug testing regime is that Drug testing used “to evaluate the root cause of a workplace incident that harmed or could have harmed employees. If the employer chooses to use drug testing to investigate the incident, the employer should test all employees whose conduct could have contributed to the incident, not just employees who reported injuries.”

Much of the current guidance seems to be common sense. Don’t use Drug Testing as retaliation for reporting an injury. Don’t drug test if the injury is not plausibly related to intoxication or impairment. For example, could Carpal Tunnel Syndrome have any conceivable connection to alcohol or illicit drug usage?

The bottom line is, get the specimen cups ready. Testing is back on the table.

If we can help you with your drug-testing or Worker’s Compensation questions, please do not hesitate to contact us.

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Wednesday, June 13, 2018

New Drug Test Case from the Georgia Court of Appeals

On June 1, 2018, the Georgia Court of Appeals published its decision in the case of Lingo v. Early County Gin, Inc., ___Ga. App. ___, 2018 Ga. App. LEXIS 328 (2018) and it may prove to be a significant decision for how drug testing will be done and viewed by the Georgia Courts in the case of an on the job injury.

The Background: Mr. Lingo worked for a Cotton Ginning company as a "module feeder." His job was to direct drivers backing their large module trucks (filled with Cotton Bales) into a loading dock area where he would then assist them with unloading of the modules of cotton for the ginning (removal of the seeds from the cotton fiber) process. Mr. Lingo was injured on November 20, 2014 when one of the trucks crushed him against the loading docks. Lingo did not see the truck as he was facing the loading dock and reportedly did not hear the truck due to two factors: 1) the truck did not have a working back-up beeper; and 2) Lingo contends that he could not hear the truck over the sound of the cotton gin machinery running nearby. He was evacuated to a hospital in Dothan, Alabama where he was taken into surgery. While in surgery, a technician who was not permitted to enter the operating room, asked a nurse inside of the O.R. for a urine sample from Mr. Lingo. The nurse brought the sample to the technician where it was marked, bagged and sent for processing. The urine sample was positive for Marijuana metabolites.

The Trial: There was conflicting evidence as to whether Lingo should have known of the presence of the truck as there was a dispute as to whether it was Lingo that directed the truck to the loading dock as part of his job. Lingo offered expert testimony in the form of a sound study regarding the noise in the area of the loading dock and from a forensic toxicologist regarding the drug test. The Sound Study Expert testified that the sound of the module truck was not distinguishable from the background noise of the cotton gin. The claimant also pointed out that the employer had offered ear plugs to protect Lingo's hearing but Lingo was not wearing them at the time. The claimant's other expert questioned whether the positive drug screen was evidence of intoxication pointing out that the marijuana metabolizes out of the blood within 30-90 minutes but will remain in the urine for days or even weeks after last consumed and so could not form the basis of a valid test. The Employer presented evidence from a co-worker who admitted to smoking marijuana with Lingo on a daily basis, who claimed that Lingo always kept a bag of marijuana on him and who claimed that Lingo "must have been really 'messed up' not to hear the truck's beeper which he argued Lingo should have heard if he was not texting on his phone." There was no evidence of marijuana or drug paraphernalia recovered from Lingo's clothing. The ALJ did not believe the co-employee, for reasons not stated in Court of Appeals opinion, but which undoubtedly included the fact that the involved vehicle did not have a working back up beeper as contended by the co-employee witness. The ALJ found the claim to be compensable and rejected the employer's drug test defense as "the lab technician did not observe the sample being taken and thre was no testimony or other evidence establishing this initial link in the chain of custody." [Let's put a pin in that and come back to it.]

The Appeals: The Appellate Division of the State Board of Worker's Compensation reversed and found the drug test to be sufficiently reliable to permit the employer to rely on the presumption afforded to the employer and against compensability in the event of a positive drug screen. The Board also noted that the evidence of whether Lingo could have heard the truck was conflicting. The Claimant appealed to the Superior Court which affirmed based on the any evidence Rule (which provides that the Courts above the State Board's Appellate division must affirm the Board's ruling if there is ANY evidence to support that ruling. The Court of Appeals is also bound by the any evidence but noted that this does not apply to errors of law.

The Ruling: The Court of Appeals was bothered by the chain of custody, noting that the Drug Free Workplace Act found at O.C.G.A. § 34-9-415 provides standards for the collection of bodily fluid samples for testing and that those standards are incorporated into the wilfull misconduct statute, O.C.G.A. § 34-9-17, upon which the employer relied in its defense. In pertinent part,O.C.G.A. § 34-9-415, provides:

All specimen collection and testing under this Code section shall be performed in accordance with the following procedures: … (5) A specimen for a test may be taken or collected by any of the following persons: (A) A physician, a physician assistant, a registered professional nurse, a licensed practical nurse, a nurse practitioner, or a certified paramedic who is present at the scene of an accident for the purpose of rendering emergency medical service or treatment; (B) A qualified person certified or employed by a laboratory certified by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the College of American Pathologists, or the Georgia Department of Community Health; (C) A qualified person certified or employed by a collection company. " That statute also provides for the chain of custody to be maintained. What troubled the Court of Appeals was that the person who took the urine sample from Lingo was never identified and their qualifications never compared with the list of required qualifications found within O.C.G.A. § 34-9-415. Remember that the technician did not go into the operating room and was handed a sample by a nurse who WAS in the operating room. Writing for the Court, Judge Ellington (Now Justice Ellington on the Georgia Supreme Court) found that "the person who actually drew the urine sample could have been a nurse's assistant, an intern, or some other hospital employee who did not meet the statutory criteria. In this case, the Employer's failure to establish that a person authorized under the Code Section to collect the sample is fatal to the Employer's ability to rely upon the rebuttable presumption in OCGA § 34-9-17 (b) (2)." The Court noted in a footnote to the decision "If, for example, the Employer in this case had identified everyone in the operating room as qualified to draw the sample, then it would be reasonable to assume that the person who drew the sample was qualified. In this case, though, there is no evidence establishing who was in the operating room."

The Impact: 1) Urine Samples Advocates for injured workers in Georgia have long argued that a urine sample is simply not competent evidence of impairment given that the fat soluable molecules of marijuana metabolites will remain in the urine for days and weeks after last usage. Once again, the Georgia Courts have rejected that assertion. The statute is clear: bodily fluid samples (saliva, urine or blood) that test positive for illicit drugs or for prescribed drugs not taken in compliance with a prescription afford the employer with a presumption that the injury was caused by the intoxication or impairment of the injured worker. Such injuries remain NOT compensable. The Employee then has the obligation to put forth evidence to rebut the presumption. That evidence must show what ACTUALLY happened and not just what MAY have happened. Had the employer been given the presumption afforded by O.C.G.A. § 34-9-17, it is unlikely that the Sound Study expert would have made the difference.

2) Chain of Custody: In all cases the chain of custody is necessary for the employer to have benefit of the presumption against compensability. Ordinarily, this chain of custody is started in the physician office when the employee hands the sample to a nurse who seals the sample with an identifiable code on that seal which matches the coding on the document to which the employee and the physician office both affix their signatures. In Lingo, it was this initial step which was missing. Thereafter the lab which retrieves the sample signs the same document and the chain of custody continues through the initial testing and all the way through confirmation testing. The significance of the Lingo ruling is that the Court recognizes that in some LIMITED circumstance, obtaining the signature may not be possible but that the defect can be overcome by other evidence and other testimony. While having the signature on the dotted line is best, we as litigants don't always get our evidence in the best of circumstances.

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Linkedin

Twitter

"Skedsvold and White

Join us on Facebook

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)